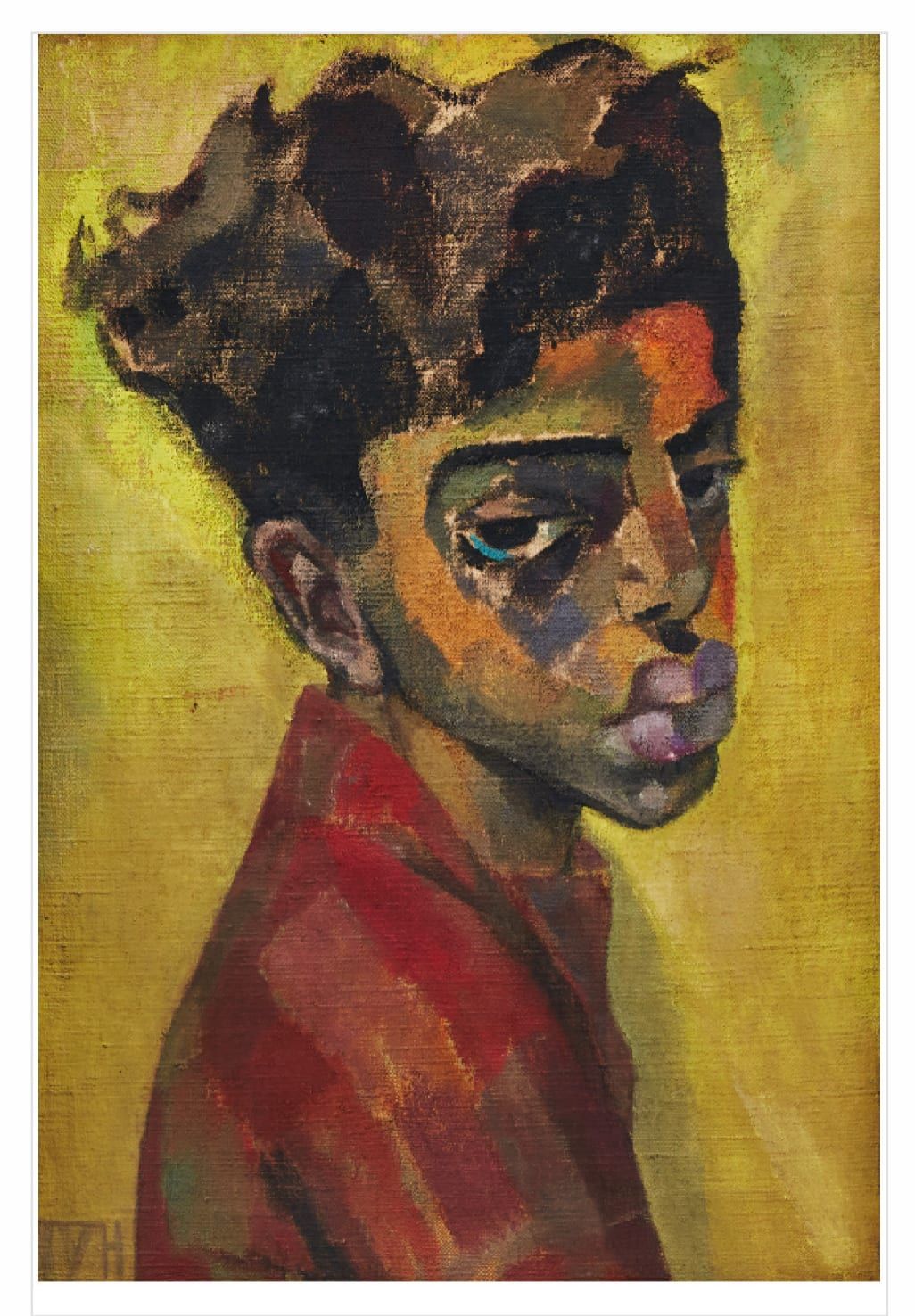

Tora Vega Holmström

Oriental

, 1929Oriental, a painting that set a new auction world record for Tora Vega Holmström when Firestorm Foundation acquired it, traces its roots back to the French Mediterranean coast. In 1924, Holmström visited the bustling Mediterranean port of Marseille in southern France for the first time. During her brief visit, Holmström became entranced by the city (to which she would return several times in the latter half of the 1920s and beyond); here was the harbour and its merging with the sea, here was a colourful oriental population, and here was light, clarity and space. Holmström’s recurring trips to Marseille would have a considerable impact on her art, affecting her palette and awakening her interest in exotic subject matter. Docent Elisabeth Lidén (born 1939, Swedish art historian and museum director) writes (in A Tora Vega E Holmström, urn:sbl:13772, Svenskt biografiskt lexikon [art av Elisabeth Lidén], hämtad 2025-07-15):

At the beginning of the 1930s, the colour scale brightened considerably. One reason for this was the trips she made to Marseille and Algeria in 1928 and 1929, respectively. The light of the South and the colourful folk life appealed to her; it strengthened her attraction to the exotic. During her trip in 1929, she painted a number of breast pictures of Negro and mulatto boys.

One of these ‘breast pictures of Negro and mulatto boys’ is the (more aptly named) Oriental in the collections of the Firestorm Foundation. Based in Madrague de Montredon (on the outskirts of Marseille), in the spring of 1929, Holmström wrote the following in a letter (dated 13 April) to fellow artist Ester Almqvist (1869–1934, Swedish artist who was a pioneer of Expressionist painting in Sweden): ‘Ester, I have now washed my brushes that were put to work today. The Negro child visited me again! I am gaining new experiences relating to my palette and its paints […]’. Although it cannot be proved, there is every reason to believe that Holmström, in her letter, is referring to the boy who modelled for Oriental.

Holmström’s fascination for oriental themes and characters can, partly, be traced back to 1920, when she visited the French garrison city of Biskra (Arabic: بسكرة) in northeastern Algeria (back then still a French colony). Some of the strong impressions of that desert city would remain with Holmström over the decade and later bear fruit during her stay in Marseille. Holmström remembered (in a letter home to Sweden in July 1929): ‘Nine years ago I spent a month in Algeria, mostly in Biskra, without painting or drawing. Now in Madrague de Mont Redon this spring, I painted something I had seen in Biskra. Two Negro soldiers listening to music. I didn’t have models; I went into Marseilles and looked at Negroes in the street. [...] There were two versions.’

The two versions that Holmström refers to are Utanför ett musikcafé i Biskra/Outside a café in Biskra (1929, oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm, Malmö Art Museum, Malmö, Sweden) and Negrer som lyssnar till musik/Negroes listening to music (1929, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 54 cm, Norrköping Museum of Art, Norrköping, Sweden). Birgit Rausing (born 1924, Swedish art historian, philanthropist, and billionaire heiress) writes (in Tora Vega Holmström, 1981): ‘She was captivated above all by the dark-skinned young people who, for her, constituted a powerful element in the street scene. One memory from her brief visit to Biskra in 1920 stood out for her-the two Negroes she had seen outside a music café. She painted them after studying the street life of Marseille.’

To put it mildly, there is something, at the very least, stereotypically stylised about these two compositions, in which genuinely individual character traits take a back seat in favour of exotizised and simplified portrayals of foreigners. This was also specifically pointed out by Camilla Hammarström, who ended her review (‘Viktig modernist som gick sin egen väg. Men utställningen på Thielska skäms av riktiga stolpskott’, Aftonbladet, 2 October 2022) of the 2022-2023 exhibition Tora Vega Holmström. Spegling är första steget mot konst at Thiel Gallery, Stockholm, by stating:

The exhibition at Thielska also includes some paintings that are problematic. They are based on sketches made by the artist on a trip to Algiers and depict Black African soldiers fighting for the colonial infantry of the French army. Here the artist falls into racial stereotypes. Those depicted lack individuality and are summarily and crudely portrayed with oversized jaws and lips. The question is, what is the point of showing such anomalies? From an artistic perspective, they are a failure. Tora Vega Holmström is an important modernist who has achieved better things. These pictures drag down the overall impression of her work.

Luckily, not all of Holmström’s production from Marseille in 1929 needs to be judged solely on the basis of these two (unfortunate) portrayals of North African people, and dark-skinned models would continue to fascinate Holmström for several decades, recurring in her art over the years. Rausing writes, ‘The Negro models would permeate Tora’s paintings - they had come to stay right into the 50s. The almost magical expressiveness of their faces was captured by Tora in several close-ups, and in their skin colour the artist often saw more orange and blue than black.’

‘The almost magical expressiveness of their faces’, as Rausing puts it, was indeed captured by Holmström in a number of ‘close-ups’. Two of these highly successful portraits, refreshingly free from any hint of stereotyping, are Oriental and (the unfortunately titled) Negerpojken Jim (Jim the Negro Boy) (1928, oil on canvas, 46 x 35 cm). These two close-up portraits from 1928 and 1929 are both characterised in a completely different way (compared to the stereotypes in the Biskra recollections) by the unique nature and distinct presence of the model. There are probably some grounds here to speak of one model as opposed to two. On closer inspection of Jim the Negro Boy, the similarities with the Oriental seem striking. The individual features and the hair undoubtedly indicate that the same boy was the model for both paintings. Considering the fact that Jim the Negro Boy has also previously been exhibited under the following titles: Gosse från Senegal (Boy from Senegal)/Jim/Negerbarn (Negro child)/Mulatt (Mulatto),it can therefore be assumed that the beautifully depicted Oriental actually had a name, Jim, and came from Senegal.

Signed (lower left corner): ‘TVH’. Also signed and dated verso: ‘TVH Marseille maj 1929’.

Provenance

The collections of Doctor Nils Stenram (1890-1966), Malmö, Sweden.

Private collection (by descent).

Uppsala auktionskammare, Stockholm, Important Sale, 8-10 November 2023, lot 608.

Firestorm Foundation (acquired at the above sale).

Exhibited

Kulturen i Lund, Lund, Sweden, Konst, konstindustri och hemslöjd-Skåne, Halland, Blekinge och Småland, 1929, no. 39.

Malmö Museum, Malmö, Sweden, Tora Vega Holmström. Oljemålningar, 13-30 March 1930, no. 43.

Literature

(Ed.) Christian Færber, Konst i svenska hem I: målningar och skulpturer från 1800 till våra dagar, 1942, listed and illustrated under collection no. 68: Doctor Nils Stenram, Malmö, Sweden, p. 93.

Birgit Rausing, Tora Vega Holmström, 1981, compare Gosse från Senegal/Jim/Negerbarn/Mulatt (1928, oil on canvas, 46 x 35 cm), illustrated p. 165 (under the title Negerpojken Jim and erroneously dated 1929).

Copyright Firestorm Foundation