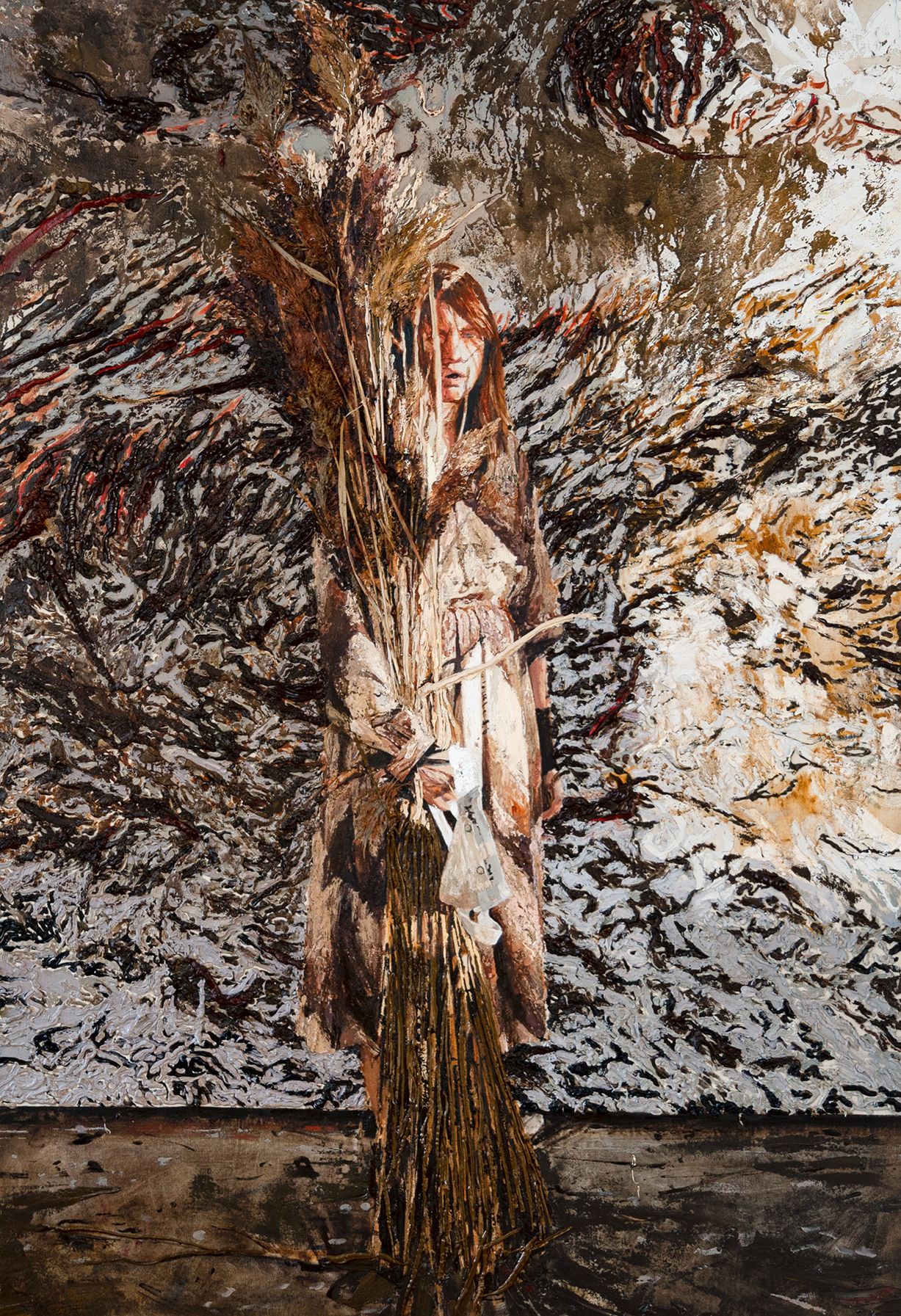

Sara-Vide Ericson

The Weaver

, 2024Sara-Vide Ericson creates her powerful and evocative paintings in an old school building (formerly owned by her aunt), large enough to serve as a residence as well as a studio, next to Lake Grängen, in the small village of Älvkarhed outside Alfta, Sweden. Here, in the heart of Hälsingland’s ancient cultural landscape, surrounded by dense forests, deep waterways, and endless fields (where flax blooms during the summer months), Ericson has found a home after a number of years spent in exile in Stockholm.

Having grown up in Rengsjö, about 40 km away from her current home, Ericson spent a lot of her upbringing roaming the local rural countryside. In an interview for the magazine Land (‘Sara-Vide Ericson: I am an extremely local artist’, 1 December 2017), Ericson told Annika Boltegård how she ‘rode out on her horse for hours after school when things were tough at home. Since then, the landscape of Hälsingland has been a backdrop for various emotional states for me. It is almost always present in my paintings.’ Her early and profound experiences of Hälsingland can explain why her later years in Stockholm were difficult for her as an artist: ‘I had a basement studio in Kungsholmen where I stood and painted the blue mountains of Hälsingland from memory—it turned out completely flat. And where was I supposed to have a coffee break in the spring sunshine, in the car park?’.

Considering how much the landscape of Ericson’s youth means to her, personally and artistically, it is reasonable to suggest that she, in Hälsingland, with its unspoiled nature and animals, early on found her own contemporary version of the mythical Arcadia (known from numerous paintings in Western art history). Arcadia (Greek: Ἀρκαδία) refers to a vision of pastoralism and harmony with nature, and the term, derived from the Greek province of the same name, dates to antiquity. The inhabitants, often shepherds, of this mythological region bear an obvious connection to the figure of the noble savage, both being regarded as virtuous and living close to nature, uncorrupted by civilisation.

Referring to herself as a hunter-gatherer, hunting, collecting, bringing home, and (when the time comes) selecting objects, experiences (or pieces of landscape) to assemble into studio paintings, Ericson could be regarded as a contemporary descendant of the ‘noble savages’ in mythological ancient Arcadia. One applicable comparison, for example, could be found in The Weaver, where the artist embraces a, recently gathered, bundle of what appears to be reeds (an assumption backed up by the fact that the tactile composition not only is built up by oil on canvas but also includes actual reeds) in the sanctity of her rural studio.

Ericson’s figurative oil paintings are also, as is often pointed out, indeed inspired by the immediate rural environment that surrounds her: the forests, rivers, and marshes of Hälsingland. However, upon closer inspection, her ‘Arcadia’ turns out to be anything but a merely well-ordered, harmonious, pastoral backdrop. As the press release for her hugely successful solo exhibition (Desire of the Tail) at Institut Suédois, Paris, put it in 2023: ‘However, her paintings are neither navel-gazing self-portraits nor naturalistic landscapes. […] Sara-Vide Ericson does not paint the “beautiful nature”, the picture-postcard nature often depicted by artists from Sweden and elsewhere. Cavernous, muddy, dangerous, even devouring, nature is an indomitable force that the artist comes to terms with more than she tries to represent it.’

The description above is further validated by Ericson’s own words: ‘I work with large-scale oil paintings that focus on inner states but in external events. The paintings usually work with or against the landscape, and in this way can highlight our inherent ambivalence towards nature and the battlefield that it is – a place where everything oscillates between destroying and being destroyed.’

That the artist views nature as a ‘battlefield where everything oscillates between destroying and being destroyed’ is referenced in The Weaver, where Ericson, clutching her reeds, seemingly poses in front of her monumental painting Soul Fracking (2024, oil on canvas, 330 x 500 cm). The title of that work, cleverly, alludes to fracking (also known as hydraulic fracturing, fracing, hydrofracturing, or hydrofracking), a well stimulation technique involving the fracturing of formations in bedrock by a pressurised liquid. The process involves the high-pressure injection of ‘fracking fluid’ (primarily water, containing sand or other proppants suspended with the aid of thickening agents) into a wellbore to create cracks in the deep-rock formations through which natural gas, petroleum, and brine will flow more freely. This method, by which humans oscillate between destroying bedrock and themselves (through the dire consequences of the method in question) has turned out to be dangerous for the environment, and the potential effects of hydraulic fracturing include air emissions and climate change, high water consumption, groundwater contamination, land use, risk of earthquakes, noise pollution, and various other health effects on humans. Interestingly enough, the reeds themselves can also be related to the artist’s view of nature as a ‘battlefield where everything oscillates’, inasmuch as they contribute to the eutrophication of Swedish waters whilst also, by scientists, recently having been deemed suitable as potential future animal feed for horses.

Works by Ericson, like The Weaver, are often hard to decipher and could be likened to objects that carry meaning from beyond the canvas. Something ancient, something wild, something you can’t quite quantify. These works challenge our perception of reality, fiction, authorship, reception, emotions, and notion of existence. The mysterious and intriguing The Weaver accordingly remains difficult to interpret, but perhaps the artist, in this piece, constructs a performative self-portrait that addresses her (as well as our own) concerns about the precarious state of our natural environment in a time of intensifying climate crisis. To, once again, quote the press release for her 2023-2024 solo exhibition at Institut Suédois, Paris:

Although Sara-Vide Ericson’s paintings are based on her own experience and sometimes feature herself, they reveal very little about her. Her inner landscapes, open to multiple interpretations, remain intriguing mysteries. In search of a form of archetype, they resonate with archaic myths, evoking a primitive and original timelessness. In this way, they are canvases which we are all invited to immerse ourselves in to explore our own connection to the world, to nature, to animals, to ourselves, to living things.

Maybe that is how one should view The Weaver? As an awakening call from the wild, where the ‘hunter-gatherer’ artist (holding on to her reeds whilst posing in front of a monumental canvas on the theme of the environmentally unsound method of fracking) silently exclaims, ‘Et in Arcadia ego’, a memento mori, or reminder of mortality even in the most beautiful and peaceful of settings.

Provenance

Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stockholm.

Firestorm Foundation (acquired from the above).

Exhibitions

Gammel Strand, Copenhagen, After the Sun, 26 September 2024-12 January 2025.

Copyright Firestorm Foundation